The Thinking Board in the Age of AI

- Michael Hilb

- Aug 31, 2025

- 6 min read

Updated: Sep 14, 2025

Boards today confront a paradox. On the one hand, they operate in an environment of radical complexity. On the other hand, directors remain human—bounded in their rationality, limited in their ability to process information, and prone to biases that shape judgment in systematic ways. Artificial intelligence (AI) promises to change this equation. By extending the reach of human cognition, they enable boards to move from a world of structural information asymmetry toward one of intelligence symmetry. Yet technology alone cannot guarantee better governance. What is needed, therefore, is the thinking board that debates assumptions, grounds itself in data, deliberates inclusively, and sustains dialogue with its stakeholders.

Bounded Rationality – Why Boards Need a Philosophy

The persistence of information asymmetry has long been central to governance theory. Jensen and Meckling (1976) explained it through agency theory: managers have superior access to information and may act opportunistically. This theory shaped regulatory responses emphasizing disclosure, auditing, and independence.

But asymmetry is not simply the result of opportunism or concealment. It also reflects the inherent limits of human cognition. Herbert Simon (1947) introduced the concept of bounded rationality: individuals cannot process all available information and must rely on heuristics to make decisions. Kahneman (2011) showed how these heuristics generate systematic biases, from overconfidence to confirmation bias.

For boards, this means that even full disclosure cannot eliminate asymmetry. Directors face cognitive overload, selective framing, and interpretive blind spots. A quarterly dashboard might show diversification, but aggregated categories could mask overexposure to a single counterparty. Reports might emphasize strategic opportunities while minimizing operational risks.

A board philosophy begins here: by acknowledging that bounded rationality makes asymmetry structural, not incidental. This recognition reframes governance not as a problem of mistrust alone but as one of cognitive capacity.

Synergic Intelligence – From Asymmetry to Symmetry

If human cognition is inherently limited, then solutions must extend beyond individual capacity. One promising avenue is synergic intelligence, where human judgment, collective wisdom, and machine intelligence are integrated into a shared system of decision-making.

Machines offer scale, speed, and predictive capacity. They process vast data sets, identify hidden correlations, and generate forecasts (Brynjolfsson & McAfee 2017).

Humans provide interpretation, contextual awareness, ethical reasoning, and strategic foresight (Davenport & Kirby, 2016).

Diversity enhances collective intelligence. Woolley et al. (2010) demonstrate that diverse groups consistently outperform homogenous ones, and Page (2007) shows how variety in perspectives improves problem-solving.

The result is what can be called intelligence symmetry: information becomes more evenly distributed and interpretable across the governance system. Directors no longer depend solely on management framing but can access a richer, multi-sourced set of insights (Hilb 2025).

Crucially, synergic intelligence does not replace human judgment but enhances it. It allows boards to move beyond their cognitive limits without abdicating responsibility.

Conditions for Synergic Intelligence in Governance

To operationalize synergic intelligence, boards must deliberately create enabling conditions. These span technology, culture, and ethics.

Technological infrastructure. Boards require integrated systems that deliver real-time, contextualized data. Studies by the McKinsey Global Institute (2018) show that data-driven organizations are more resilient and innovative. For governance, this means access to dynamic dashboards that combine financial, operational, and stakeholder information.

Cultural adaptation. Infrastructure alone is insufficient. Directors must be data literate and digitally fluent. Bhimani (2021) emphasizes the importance of digital acumen in finance and governance. Boards that resist technological integration risk being outpaced by complexity. A philosophy of governance today requires a mindset of continuous learning and openness to augmentation.

Ethical guardrails. The OECD (2019) highlights the risks of opaque AI systems: accountability can be undermined, and biases perpetuated. Governance must ensure explainability, fairness, and responsibility in the use of algorithms. Ethical oversight is not optional; it is a fiduciary duty.

Without these conditions, synergic intelligence may create new asymmetries. For example, directors might defer blindly to algorithmic outputs without understanding underlying assumptions, reinforcing rather than reducing risk.

Implications for Board Members

The implications for directors are profound and extend well beyond technical adaptation.

From oversight to co-creation. Boards must move from passively reviewing management reports to actively shaping insights. Directors become co-creators of governance intelligence, interrogating models, and testing scenarios (Hilb 2020).

From credentials to competencies. Traditional qualifications such as industry tenure or financial expertise remain important but are insufficient. Competencies in digital literacy, risk framing, and systemic thinking are essential for modern governance.

From homogeneity to heterogeneity. Diversity becomes a strategic capability. Page (2007) and Woolley et al. (2010) provide strong empirical evidence that heterogeneous groups outperform homogenous ones in complex problem-solving. For boards, diversity is not only about representation—it is about resilience and insight.

From episodic to continuous engagement. Traditional governance often revolved around periodic oversight. Intelligence symmetry allows for continuous dialogue and reflection, shifting the role of directors toward ongoing strategic stewardship.

Thus, the board does not need philosophers who speculate in abstraction. It needs directors who can apply a philosophy of practice: grounded in awareness of cognitive limits, enriched by collective intelligence, and disciplined by ethical responsibility.

A Framework for the Thinking Board

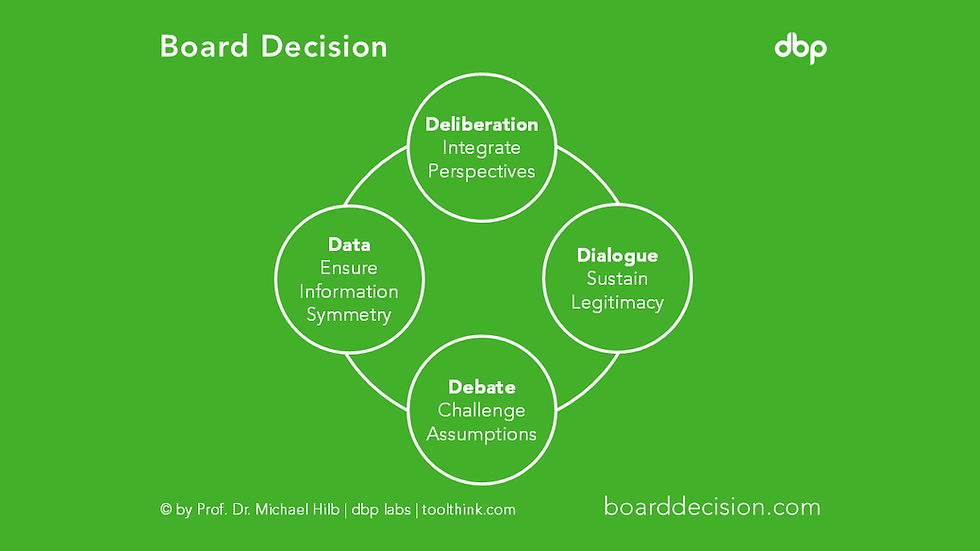

If boards are to move from bounded rationality toward intelligence symmetry, they need more than scattered best practices or fashionable tools. They require a disciplined way of structuring how they think and act together. The Debate–Data–Deliberation–Dialogue framework is one such method. It translates abstract philosophical principles into actionable routines that make the boardroom a site of collective intelligence rather than fragmented judgments.

Debate – Challenging Assumptions

Effective governance begins with recognizing the limits of human cognition. Debate is not about adversarial posturing, but about making assumptions explicit and testable. By encouraging directors to ask, “What if the opposite were true?” or “What are we not seeing?”, boards acknowledge the structural presence of bias and blind spots. Structured dissent, devil’s advocacy, and red-teaming exercises can help uncover hidden vulnerabilities in management’s framing of reality. Debate creates the cognitive tension necessary for avoiding complacency.

Data – Ensuring Information Symmetry

Debate must be grounded in facts, not only opinions. This requires the systematic design of information flows that are timely, transparent, and relevant. Advanced dashboards, AI-driven analytics, and scenario models are useful—but only if directors understand their scope and limitations. Data symmetry means management and board alike draw from a shared evidence base rather than selective curation. Here, the role of the board is to ensure not just access to information, but also the quality, comparability, and interpretability of that information.

Deliberation – Integrating Perspectives

Data alone does not generate insight. Boards add value by deliberating across diverse viewpoints, blending human judgment with algorithmic outputs. Deliberation is the act of weighing trade-offs, balancing short- and long-term implications, and situating numbers within narratives. It requires inclusivity—inviting dissent, encouraging minority voices, and leveraging the diversity of backgrounds around the table. Deliberation transforms raw data into collective judgment, while ensuring responsibility is not outsourced to machines.

Dialogue – Sustaining Legitimacy

Finally, governance cannot end when the meeting does. Dialogue extends board thinking into continuous engagement with management, shareholders, employees, regulators, and society. It is about legitimacy as much as insight. Boards that cultivate authentic dialogue signal that decisions are not made in isolation but in awareness of their systemic consequences. Dialogue also builds organizational learning: insights from past debates, data, and deliberations feed into future decisions, creating an adaptive governance cycle.

Together, these four elements form a cycle rather than a sequence. Debate sharpens the questions; data grounds them; deliberation integrates perspectives; and dialogue sustains legitimacy and learning. This cycle can be repeated across strategic decisions, risk oversight, and crisis response, providing both consistency and adaptability. This framework operationalizes philosophy in the boardroom. It provides discipline without dogma and structure without rigidity.

Conclusions

Boards today operate in an environment characterized by complexity, disruption, and heightened scrutiny. Human bounded rationality ensures that information asymmetry will persist if governance relies solely on individuals. But synergic intelligence—integrating human, machine, and collective capacities—offers a path toward intelligence symmetry.

To realize this potential, boards need a philosophy: an explicit recognition of limits, a commitment to shared intelligence, and a framework for disciplined practice. But they do not need philosophers in the traditional sense. Abstract speculation without application risks paralysis. What boards need are directors who think philosophically in action—challenging assumptions, engaging with data, deliberating inclusively, and maintaining dialogue.

The paradox thus resolves itself: By acting as a thinking board, boards can not only fulfill their fiduciary duties but also shape organizations that thrive in the age of artificial intelligence.

References

Bhimani, A. (2021). Accounting Disrupted: How Digitalization is Changing Finance. Wiley.

Brynjolfsson, E., & McAfee, A. (2017). Machine, Platform, Crowd: Harnessing Our Digital Future. Norton.

Davenport, T. H., & Kirby, J. (2016). Only Humans Need Apply: Winners and Losers in the Age of Smart Machines. Harper.

Hilb, M. (2025): Transitioning to intelligence symmetry: How AI can reshape corporate governance. Forbes, September 9.

Hilb, M. (2020): Toward artificial governance? The role of artificial intelligence in shaping the future of corporate governance. Journal of Management and Governance. 24, 851–870.

Jensen, M. C., & Meckling, W. H. (1976). Theory of the Firm: Managerial Behavior, Agency Costs and Ownership Structure. Journal of Financial Economics, 3(4), 305–360.

Kahneman, D. (2011). Thinking, Fast and Slow. Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

McKinsey Global Institute (2018). Notes from the AI Frontier. McKinsey.

OECD (2019). Principles on Artificial Intelligence. OECD Council Recommendation.

Page, S. E. (2007). The Difference: How the Power of Diversity Creates Better Groups, Firms, Schools, and Societies. Princeton University Press.

Simon, H. A. (1947). Administrative Behavior. Macmillan.

Woolley, A. W., Chabris, C. F., Pentland, A., Hashmi, N., & Malone, T. W. (2010).

Evidence for a Collective Intelligence Factor in the Performance of Human Groups. Science, 330(6004), 686–688.

The author employed AI-based writing tools to support the drafting process. All core ideas, arguments, and conceptual contributions are solely those of the author.

Comments